A short follow-up to my post last week.

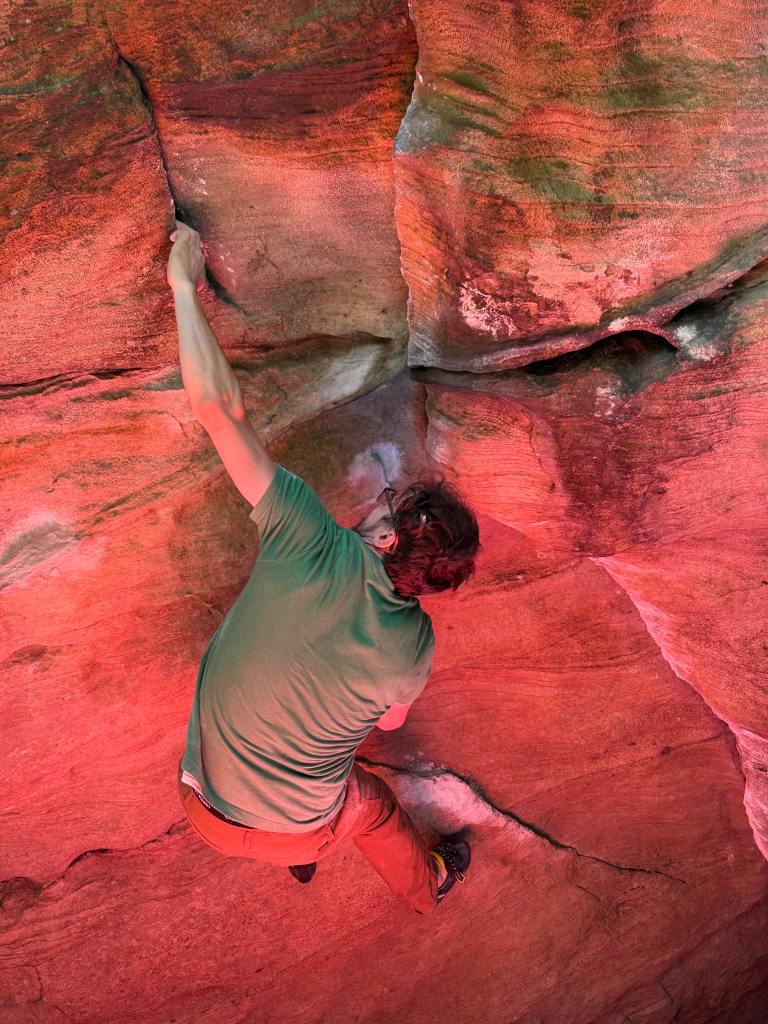

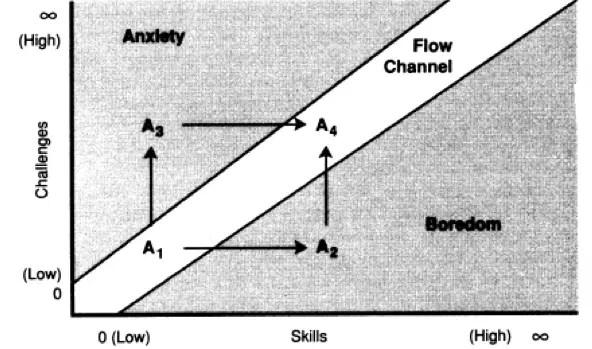

A couple of days ago I eked out a send of my first outdoor 5.12. It wasn’t the most inspiring climb, and it’s almost certainly a bit soft for the grade, but it’s an experience I’ll remember. The route is defined by a distinct crux down low — a v4 boulder problem that involves making a big move off of awkward crimps to a jug, then a couple of powerful moves to a rest. I’m a relatively strong boulderer, at least for this level of difficulty, so I was able to quickly figure out a reliable sequence. What I didn’t count on was the other two-thirds of the climb being difficult to read. I didn’t bother working the top, figuring that I should save energy and simply on-sight the 5.10 climbing above. This, I now realize, was a mistake. (I’m still relatively new to ‘redpoint’ tactics on harder routes.) It’s not a climb often done, so the upper part of the route turned out to be lichen-covered, ambiguous, and relatively chossy. Thinking the top would be a victory lap after the crux, I charged up after the rest and ended up off-route, well above the previous bolt, and unable to clip the next piece of protection. Perhaps because of adrenaline, perhaps because of nerves, one of my legs started to involuntarily shake when I was about to make a committing move in this precarious position. (Climbers call this ‘Elvis leg.’) While my mind felt relatively clear and focused, my body began to physically react to the situation. I took the cue, calmed myself, and down-climbed back to the rest to find another path. I ended up finding another way up, though still not particularly smoothly. In the end, perhaps not the wisest choice, I ended up skipping a bolt and going straight for the chains.

I’m jotting down this anecdote for a few reasons:

1. First, one of my general long-term athletic goals is to become a solid 5.12 climber—to be able to confidently jump on any 5.12a–5.12d and feel comfortable working the moves. This was my first 12a on lead, and it feels like crossing a little milestone.

2. Second, in line with my post last week, the experience is a vivid demonstration to me that technique, more than strength, is a bottleneck for my progression. Of course, it always helps to be stronger, more flexible, leaner, and so on, but it’s more evidence that those are probably not where I should place emphasis.

3. And third, it’s one of the first times as an adult where I’ve felt my body responding completely differently from my mental state. My mind felt relatively calm, even when I had made a mistake. My body, however, was clearly feeling something different entirely. The last time I felt this kind of radical disconnection, at least that I can remember, is the social anxiety that followed me as a young person. As a lifelong introvert, I’d always feel my body react when I was asked to say something in front of any group larger than a handful of people. Heart pounding. Hair raised. Throat dry. It took years for me to be able to understand, separate, and adapt to those physical responses so I could perform in front of groups. I still feel those reactions to this day, even when I’m doing something as routine as lecturing. Those experiences as a young person continue to help me now, in pursuits as diverse as rock climbing, dealing with family drama, or navigating faculty politics. It’s a simple insight, but one that continues to serve me well: Physical reactions are *information* that can be embraced, ignored, or channeled.