Over the last year I’ve populated my nightstand with various books on mental health. A few days ago I picked up a classic: Flow: The psychology of optimal experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Briefly, Csikszentmihalyi’s aim is to understand “optimal experience” — what the sailor feels when the wind whips through her hair, what the painter feels when the colors on the canvas begin to come to life, what the rock climber feels when they unlock a cryptic sequence of moves to ascend the sheer face of a cliff. Optimal experiences, the author argues, “usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile. Optimal experience is thus something that we make happen” (3).

I still have a number of pages left in the book, but the following passage caught my eye:

Cultures are defensive constructions against chaos, designed to reduce the impact of randomness on experience. They are adaptive responses, just as feather are for birds and fur is for mammals. Cultures prescribe norms, evolve goals, build beliefs that help us tackle the challenges of existence. In so doing they must rule out many alternative goals and beliefs, and thereby limit possibilities; but this channeling of attention to a limited set of goals and means is what allow effortless action within self-created boundaries. […]

A culture that enhances flow is not necessarily “good” in any moral sense. The rules of Sparta seem needlessly cruel from the vantage point of the twentieth century, even though they were by all accounts successful in motivating those who abided by them. The joy of battle and the butchery that exhilarated the Tartar hordes or the Turkish Janissaries were legendary. It is certainly true that for great segments of the European population, confused by the dislocating economic and culture shocks of the 1920s, the Nazi-fascist regime and ideology provided an attractive game plan. It set simple goals, clarified feedback, and allowed a renewed involvement with life that many found to be a relief from prior anxieties (81-82).

At the crag I’ve often joked that climbing is a kind of cult. Gumbies are lured in and, eventually, become radicalized. Devotees adjust their diet, their exercise regimen, their information environment, and their free time in pursuit of an optimal climbing experience. In training one’s body, the mind begins to follow. Priorities. Assessments of risk and reward. The meaning of pleasure. Of pain.

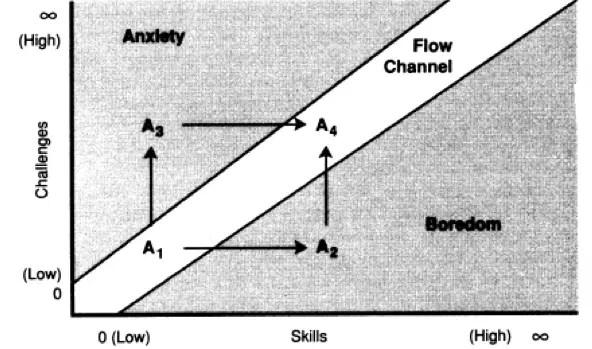

To my mind, Csikszentmihalyi’s account shows at least one dimension of why, precisely, some ideologies are so seductive. By aligning tasks with difficulty (the author’s famous chart is reproduced above), they draw us in deeper. They provide a path to ‘optimal experience’, to flow. An effective ideology pulls on our subconscious, often without our awareness, and in so doing structures possibilities, shapes decision-making, and influences our response to reasons. While attributing this to climbing culture might be hyperbole, I don’t think it’s wildly off the mark for a number of other contexts in our midst. The anti-feminist radicalization of young men online through red-pill, MGTOW, and incel communities, is one example, or the exercise and dietary prescriptions of various theocratic regimes is another. One simple upshot is that flow is an under-appreciated, but potentially powerful mechanism of ideological maintenance.

Leave a comment