The mass protest decade: why did the street movements of the 2010s fail? | Protest | The Guardian

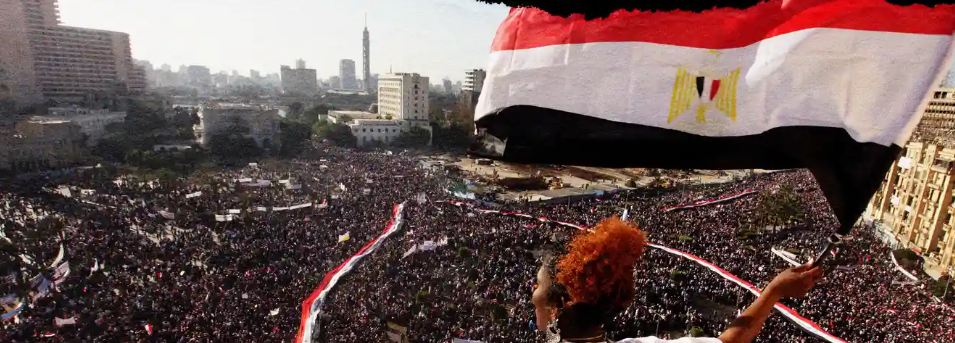

This is an interesting article I saw in The Guardian about the global protest movements of the 2010s, a decade that saw protests move from the Middle East to the Americas and Asia. Many of these protests achieved something. Governments fell in the Tunisia and Egypt, governments reversed course in Latin America, and income inequality became a salient political issue in the United States. Yet for all the successes achieved by these movements in the moment, many have come to see their lasting outcomes as disappointing, or as the article’s author puts it “In many cases, things got much worse.”

So where did these movements go off track? Did they even go off track in the first place or did other factors and forces within society catch up and overtake them? The discussion within the article moves from the disappointment of the movements to ideas about different organizational forms that these movements take. In many cases, the author argues, these movements were motivated by a commitment to ‘true democracy’ or a radical version of collective decision-making. This ‘horizontalism’ is contrasted with the ‘verticalism’ of other historical social movements like the Leninist Communist Party, with their declared leaders/spokespersons and hierarchical forms.

The article prompted to me to think about leverage and how certain social and organizational forms are good for some things, but very bad for others. “The particular repertoire of contention that became very common from 2010 to 2020 – apparently spontaneous, digitally coordinated, horizontally organised, leaderless mass protests – did a very good job of blowing holes in social structures and creating political vacuums. But it was much less successful when it came to filling them.” Indeed, these leaderless mass protests probably achieved what they achieved precisely because of this particular repertoire of contention, which allowed the movements to capitalize on multiple grievances against the existing order, attract an overwhelming base of support, and mobilize thousands.

Despite the successes of these movements and their ability to bring about change (and they did bring about change, startling and momentous change in many cases), these movements were destined to flame out. Attempts to take the movement in a single direction would alienate some supporters. Even a commitment to a radical notion of ‘true democracy’ is bound to give some who supported a movement against the existing order second thoughts. Moreover, the opportunity opened up by these movements, particularly in situations where governments fell, allows those who have organized and can move in a single direction an advantage. This happened in Egypt, both with the election of the Muslim Brotherhood government and then the reactionary military coup.

In the US, it could be argued the anti-elitism of the Occupy Wall Street movement sapped energy from Hillary Clinton’s campaign for the presidency in 2016. However, we would have to trace how protests in 2011-12 carried over into both the Clinton/Sanders Democratic primary and the 2016 general election.

Leave a comment