In the late spring I severely sprained my ankle. A little carelessness at an unfamiliar bouldering gym led to a frustratingly avoidable mistake. I hobbled around the first week on crutches, then managed to get by with a limp. Eventually I was able to climb, but only on top rope and only by hopping around on one foot. After a month or so, I was able to gently weight my foot on climbing holds and start leading again. As a consequence of the ankle, however, I had to be much, much more intentional with foot placements. I had to literally look at my foot for every placement. This had an unexpected effect. After climbing in this more slow, deliberate style for only a few weeks, despite not being at full strength, I found that I was actually climbing the same grade, if not harder, than I was before. It had never occurred to me that a lack of precision, or a lack of explicit attention to my feet, was leading to simple mistakes. When I was able to take this new pattern of slower, more deliberate footwork outside a month later, I immediately was able to succeed on much harder routes.

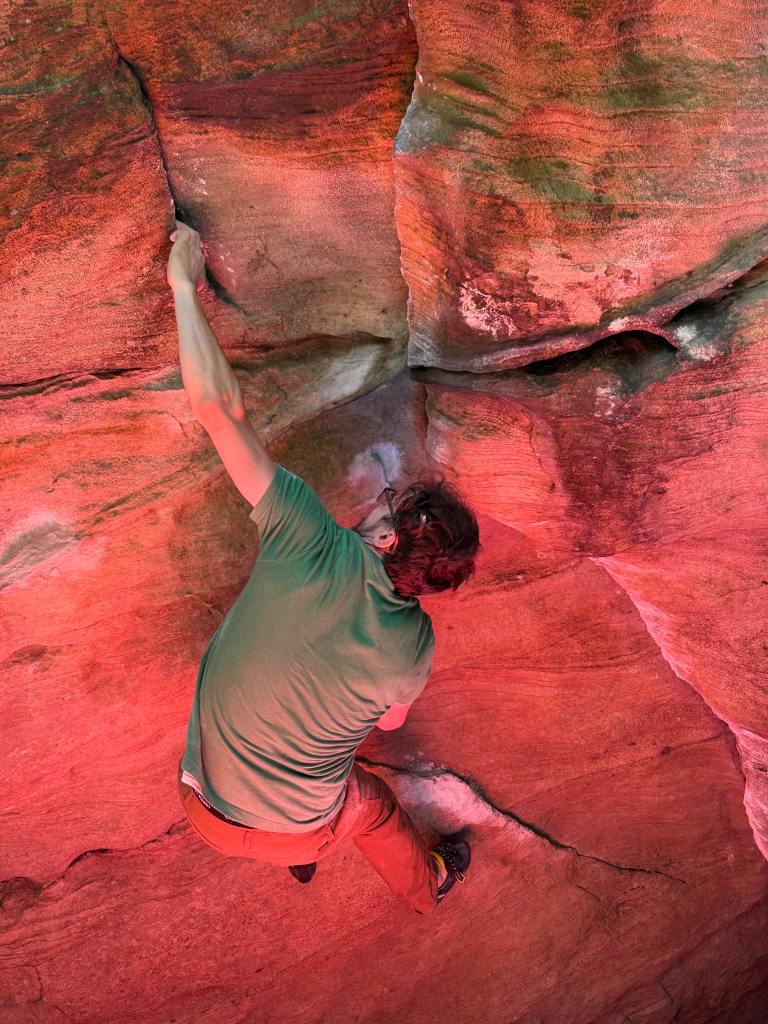

About three months after the initial injury, I decided that my ankle felt strong enough to boulder again, but that it was still too risky to take larger ground falls. My response was to focus on the 12×12-foot ‘system boards’ (a Kilter board and a Tension 2) in my local gym, which can be tilted to 40–50 degrees. At those angles, this means your feet are never much more than 3–4 feet off the ground. Minimum risk, I thought, and I could get back to bouldering. I had played on the boards before, but never consistently. As with the rope climbing while still recovering, I quickly noticed that the steep boards exposed a number of weaknesses. Of course, I was weaker from not bouldering for months. But I also noticed limitations in basic flexibility, core strength, and particular body positions, not to mention basic finger strength. Simply working the boards for two days a week, no more than an hour or so, has led to straightforward improvements. After about two months only bouldering on the system boards, I’m now not only as strong as I was before being injured, but arguably stronger. And the boards are actually a lot more fun than I realized. As the fall climbing season begins, I’m now in a position to try local bouldering projects that last year were well out of reach.

So, what do I make of all this? Earlier in the year I read Ericsson and Pool’s Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. In that book, the authors make the distinction between ‘purposeful’ practice and ‘deliberate’ practice:

With this definition we are drawing a clear distinction between purposeful practice — in which a person tries very hard to push himself or herself to improve — and practice that is both purposeful and informed. In particular, deliberate practice is informed and guided by the best performers’ accomplishments and by an understanding of what these expert performers do to excel. Deliberate practice is purposeful practice that knows where it is going and how to get there (98).

For a lot of people, myself included, there is a misunderstanding about practice. They hold the (often implicit) belief that simply by being consistent you’re bound to improve. For example,

They assume that someone who has been driving for twenty years must be a better driver than someone who has been driving for five, that a doctor who has been practicing medicine for twenty years must be a better doctor than one who has been practicing for five, that a teacher who has been teaching for twenty years must be better than one who has been teaching for five (13).

But, Ericsson and Pool write, the evidence suggests that’s wrong. They write that the body of academic research on the subject shows that, generally speaking, once a person reaches that level of “acceptable” performance and automaticity, the additional years of “practice” don’t lead to improvement. In fact, in the absence of deliberate practice, the person who has been at it longer may actually be worse off. Without intervention, cultivated habits can deteriorate.

I didn’t realize it until recently, but my post-injury response shifted my behavior from simply being (loosely) purposive with my climbing to being more deliberate. I was accidentally and haphazardly following tried-and-true methods coaches use to train intermediate-to-advanced climbers and seeing direct gains as a consequence. I wish it didn’t take an injury to discover these basic insights, but I’m glad something positive has come from it. I’m not really interested in turning an activity that I enjoy into a chore — you’re never going to see me doing long, grueling hangboard workouts — but these last few months have impressed upon me how powerful habit mixed with even a little deliberate practice can be for athletic performance. As my ankle fully recovers, hopefully it’s a lesson I can carry forward.

Leave a comment